Pro Memoria

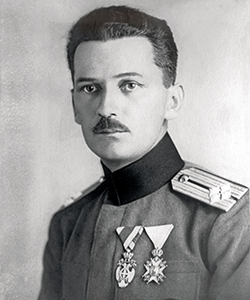

MILADIN PEĆINAR (1893-1973), ACADEMICIAN, PIONEER OF SERBIAN HYDROLOGY ENGINEERING, WAR HERO, VISIONARY

The Architect Who Built with Goodness

Nothing educates us as deeply as the examples of great ancestors, simple and unconditionally dedicated. This little boy from Ljubiš on Zlatibor became one of the 1.300 corporals in World War I, attended great schools, built many dams and hydroelectric power plants in two Yugoslavias, waterworks in many cities, the Sava Lake in Belgrade and the one in the center of Zlatibor. He was member of SANU, published many scientific works in engineering. He also wrote an important book-testimony, with many signs along a difficult path. And he is lasting

By: Miloš Lazić

Photo: Private archive

When one mentions Ada Ciganlija, the first thought that comes into mind is the Sava Lake, inventively called the Belgrade Sea. However, the branch of the Sava in Čukarica was not dammed for the Belgradians to get another beach, but to have enough healthy drinking water. It is more important as a hydrological than as a tourist destination, the biggest tank of drinking water for the Serbian capital city. From the end of the XIX century and from the founding of the modern city waterworks in 1892, it was the most significant endeavor for supplying the overcrowded city with water, the basis of the present ”water factory”. It was established seven decades later, when the Sava branch was dammed, and in 1967 became a natural water tank.

When one mentions Ada Ciganlija, the first thought that comes into mind is the Sava Lake, inventively called the Belgrade Sea. However, the branch of the Sava in Čukarica was not dammed for the Belgradians to get another beach, but to have enough healthy drinking water. It is more important as a hydrological than as a tourist destination, the biggest tank of drinking water for the Serbian capital city. From the end of the XIX century and from the founding of the modern city waterworks in 1892, it was the most significant endeavor for supplying the overcrowded city with water, the basis of the present ”water factory”. It was established seven decades later, when the Sava branch was dammed, and in 1967 became a natural water tank.

The big venture was designed by academician Miladin Pećinar, a great architect, one of the pioneers of Serbian hydrology engineering, one of the heroes from the famous ”1.300 corporals”.

His most important hydro-technical objects are enlisted in his ”official biography”, including the pre-war port dam ”Matka” with the ”Sveti Andreja” hydroelectric power plant on Treska, hydroelectric power plants ”Čečevo” near Kosovska Mitrovica, ”Novi Pazar” in Raška, ”Temštica” in Pirot, ”Perućačko Vrelo” in Bajina Bašta, and ”Crni Timok” in Boljevac, as well as the waterworks in Skopje, Tetovo, Užice, Belgrade, Obrenovac... More than enough for two human lives.

There are at least two especially remarkable things in the biography of academician Miladin Pećinar. The first is that, already as first year student of civil engineering, he was mobilized as member of the famous Students’ Battalion, also known as ”1.300 corporals”, a unit which represent one of the most touching examples of Serbian patriotism in World War I. The second was saved from oblivion by poet Ljubivoje Ršumović, his neighbor from the Zlatibor village of Ljubiš, when writing a prologue for Pećinar’s chronicle-autobiography From Serbia to Yugoslavia.

There are at least two especially remarkable things in the biography of academician Miladin Pećinar. The first is that, already as first year student of civil engineering, he was mobilized as member of the famous Students’ Battalion, also known as ”1.300 corporals”, a unit which represent one of the most touching examples of Serbian patriotism in World War I. The second was saved from oblivion by poet Ljubivoje Ršumović, his neighbor from the Zlatibor village of Ljubiš, when writing a prologue for Pećinar’s chronicle-autobiography From Serbia to Yugoslavia.

”Wishing to help his fellow villagers of Ljubiš, especially children, he built a public bath for students in the schoolyard. He captured the spring under Smiljansko Brdo and brought water, installed tubs and showers... The bath started working before World War II! The war and armies destroyed it, but people kept the memory of the benevolence of young engineer Miladin Pećinar.”

The academician completed his unusual confession in 1973, at the age of eighty. He died in the middle of the same year. Unfortunately, three decades had to pass before his work found itself between book covers. Perhaps because, when his acquaintance, volunteer nurse Little Joy, invited him to come and stay in Canada with his family after the war, he thanked her and recklessly used the expression ”post-war occupation”?

A TREE RICH IN FRUIT

In the List of Important People of the Serbian Nation, written by academician Milan Đ. Milićević in 1888, as well as the revised editions of the book in the XX century, a careful reader will certainly notice that only a few of those people originate from cities. The countryside has always been an inexhaustible reservoir of the nation’s wisdom and vitality. Thus it doesn’t sound incredible when academician Pećinar ascribes poetic and philosophical features to his grandfather Dimitrije, only seemingly imbued with the ideas of social-democracy. Of course not! The feeling for social justice comes from the being of this nation, from the experiences gained for centuries in family corporations, in which he was also born and spent his childhood.

In the List of Important People of the Serbian Nation, written by academician Milan Đ. Milićević in 1888, as well as the revised editions of the book in the XX century, a careful reader will certainly notice that only a few of those people originate from cities. The countryside has always been an inexhaustible reservoir of the nation’s wisdom and vitality. Thus it doesn’t sound incredible when academician Pećinar ascribes poetic and philosophical features to his grandfather Dimitrije, only seemingly imbued with the ideas of social-democracy. Of course not! The feeling for social justice comes from the being of this nation, from the experiences gained for centuries in family corporations, in which he was also born and spent his childhood.

The Pećinar family tree sprouted in the late XVII century, after the Austrian defeat from the Ottomans in the Battle of Vienna, when three sisters-in-law, Smiljana, Ojdana and Jasna, whose last names remain unknown, moved from Kotor to Metohija. From there (according to anthropologic and geographic investigations of Ljubomir Ž. Mićić), some of their descendants moved to Zlatibor in the late XVIII century, in the eve of the First Serbian Uprising.

The genealogical tree then branched. Some were poor, some rich, some self- and some officially educated. Dimitrije’s passport issued in 1866 is still preserved. He traveled to Turkey with it as a tailor, probably along with certain state affairs, since the travel document was personally signed by Ilija Garašanin, minister of foreign affairs at the time!

Dimitrije’s son Mijailo, Miladin’s father, was a literate, hard-working, yet hard to deal with man, something his grandfather often criticized. He was president of the village municipality for two decades. As member of the progressive party, he tried to introduce discipline and educate people using harsh measures, fighting against chaos and laziness. He dug roads through the village and fixed the river beds and flood canals so skillfully, that even experts came to study his work. The ideas he applied when building the mill in the village center were a wonder for civil engineers. That thread continued in his son Miladin.

Mijailo died in the eve of the Balkan Wars, at the time politics included weapons. Since then until the First Balkan War, Miladin held classes for rich gymnasium students in Užice and thus supported his mother, younger sister and brother.

THE CURVY DRINA

Academician Pećinar dedicated the most voluminous chapters of his chronicle to the liberation and defensive wars of the Kingdom of Serbia from 1912-1918. He participated in both Balkan wars as member of the ”last defense” and in the Great War as a soldier, non-commissioned officer and officer. He previously described his first trip across the Serbian border shortly before the war.

Academician Pećinar dedicated the most voluminous chapters of his chronicle to the liberation and defensive wars of the Kingdom of Serbia from 1912-1918. He participated in both Balkan wars as member of the ”last defense” and in the Great War as a soldier, non-commissioned officer and officer. He previously described his first trip across the Serbian border shortly before the war.

A year after the annexation of Bosnia, he got his father’s approval to travel over the Drina. From the always wondrous Višegrad bridge, through Počitelj, the spring of Buna, Mostar and Konjic, to Sarajevo. He later wrote with sadness that he would have settled in Ilidža, only if hydrology engineering hadn’t tied him to Belgrade. Later events showed that he was actually very lucky.

Before high school graduation in 1912, he participated at the All-Slavic Sokol Slet in Prague, and returned encouraged by Czech hospitality and sincere Slavic solidarity. In the middle of that year, he enrolled in the Technical Faculty in Belgrade, civil engineering department. It was, as he noted then, the last regular event in his life. ”After it came irregular events lasting to the very day”, he wrote, thinking of three wars that followed and the fourth which some had already anticipated.

In his war stories, Miladin wrote about ordinary people, his fellow-soldiers and spoke from his heart and not from the army coat, as others did. The most striking one from his first year of warfare describes the bloody battle on Crni Vrh above Priboj, already conquered by two Austro-Hungarian regiments, which then started towards Nova Varoš and Prijepolje. The 4th regiment, consisting of the oldest soldiers from Užice, was waiting for them. The battle was such that both sides thought they were defeated. Many people from Ljubiš died, which made the battle even more memorable for him. The epilogue was discovered only after the war and uniting, when young engineer Pećinar heard some Croatians say: ”Those who were not in the battle in Crni Vrh don’t know the meaning of war!”

In his war stories, Miladin wrote about ordinary people, his fellow-soldiers and spoke from his heart and not from the army coat, as others did. The most striking one from his first year of warfare describes the bloody battle on Crni Vrh above Priboj, already conquered by two Austro-Hungarian regiments, which then started towards Nova Varoš and Prijepolje. The 4th regiment, consisting of the oldest soldiers from Užice, was waiting for them. The battle was such that both sides thought they were defeated. Many people from Ljubiš died, which made the battle even more memorable for him. The epilogue was discovered only after the war and uniting, when young engineer Pećinar heard some Croatians say: ”Those who were not in the battle in Crni Vrh don’t know the meaning of war!”

From the expulsion of the last foreign soldier from Serbia on December 2, 1914, to the great enemy offensive ten months later, typhoid fever took away more lives than the enemy bullets had during the entire previous warfare!

BLOODY PATHS

He wrote with sadness about the chaos during the retreat of the army, people and state at the end of 1915. The only bright moment was the encounter with five of his friends from the Užice gymnasium in Matoševa, under Trešnjevik. (He will later find out that he was the only one who returned from the war alive.) He described the retreat through Montenegro, listening to the whispers of soldiers about the relations of two brother countries and two dynasties from the same family, without giving his personal judgment. However, he couldn’t keep quiet about the bargaining of allies with the Serbian army, especially not about the price of the treacherous attitude paid with human lives. He witnessed mortal pains of the wounded, sick and exhausted combatants.

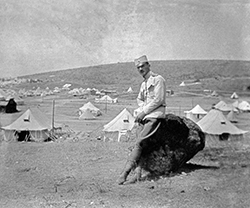

The road to Corfu ended on Vido, ”the island of death” or ”blue tomb”, for one quarter of Miladin’s fellow soldiers. Exhaustion and cholera finished the previous work of wounds and typhoid fever. Miladin also almost died from hepatitis! However, although sick, he ran away from the hospital and reached his unit, which already made a camp near Thessalonica. He had enough time to gain a bit of his strength back and begin preparations for the breakthrough of the front.

The road to Corfu ended on Vido, ”the island of death” or ”blue tomb”, for one quarter of Miladin’s fellow soldiers. Exhaustion and cholera finished the previous work of wounds and typhoid fever. Miladin also almost died from hepatitis! However, although sick, he ran away from the hospital and reached his unit, which already made a camp near Thessalonica. He had enough time to gain a bit of his strength back and begin preparations for the breakthrough of the front.

Sublieutenant Miladin Pećinar did not deal with strategy, tactics and politics, but with people. He was seriously wounded near Gorničevo, but didn’t describe it in detail in his chronicle. We know it had almost cost him his right leg, but probably saved his head. We know about the breakthrough of the Thessalonica Front and liberation of our homeland, how much courage and lives was built into it. He didn’t want to go to Biserta, where they sent him to recover, but stayed in Thessalonica and rearranged a temporary camp near the city into a real war infirmary. Even the minister of war affairs stopped by to rest there. Only in the spring of 1917, he accepted to go to Rome with a group of students to continue his education.

He soon realized that Serbs in Italy are very reputable, but also understood the games regarding pushing them into Yugoslavia. Warfare seemed more honest and better than the battles led at negotiation tables of secret diplomacy. He met Benito Mussolini, young socialist at the time, who will later become famous for some other things.

CLIMAX OR GATES OF DESTRUCTION

Academician Pećinar’s chronicles also show that the allies gave up on the Thessalonica Front and planned to move the focus of the battles to the west. But who dared to move the Serbian soldier from there, almost at the doorstep of his occupied homeland, after the first successes in the trenches battles with Bulgarians? Then came duke Živojin Mišić, celebrated strategist from Kolubara, and marshal Franchet d'Espèrey, commander of the front, accepted his plan. ”We, students, didn’t have the honor to participate in this final heroic endeavor. We felt it strongly”, wrote Miladin in those days.

Academician Pećinar’s chronicles also show that the allies gave up on the Thessalonica Front and planned to move the focus of the battles to the west. But who dared to move the Serbian soldier from there, almost at the doorstep of his occupied homeland, after the first successes in the trenches battles with Bulgarians? Then came duke Živojin Mišić, celebrated strategist from Kolubara, and marshal Franchet d'Espèrey, commander of the front, accepted his plan. ”We, students, didn’t have the honor to participate in this final heroic endeavor. We felt it strongly”, wrote Miladin in those days.

The breakthrough of the front began on September 1, 1918, and on November 1, the Serbian army entered Belgrade. Less than a month later, the peace treaty was signed in the vicinity of Paris, which put an end to the Great War. Then followed the uniting of the southern-Slavic territories into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croatians and Slovenians, later Kingdom of Yugoslavia, already on December 1, 1918. It seemed that Serbia was on the climax of its glory and greatness.

This is where the confession of academician Miladin Pećinar ends.

He did not give his judgment about the uniting, except for short information, although the thought that vanity and political aspirations of the sovereign overpowered reason is present in the book. Miladin Pećiner completed his education and his great civil engineering endeavors began. His life and deed are still brightly standing in front of us. We remember him each time we take a walk at the Sava Lake or the one in the center of Zlatibor. Nothing educates us as deeply as the examples of our great ancestors, simple and unconditionally dedicated.

***

Path

Miladin Pećinar was born in 1893, in the Zlatibor village of Ljubiš, where he finished elementary school and graduated from the gymnasium in Užice (1912). He enrolled in the Civil Engineering Department of the Technical Faculty in Belgrade, but his education was interrupted by the wars. He participated in the wars and was seriously wounded on the Thessalonica Front in 1917. He was promoted into the rank of reserve infantry major after the war. He continued his studies first at the Applied School for Civil Engineers in Rome, then at the Civil Engineering Department of the Technical Faculty in Belgrade, and completed them in 1921. He became involved in hydrology engineering and in 1925 opened his Bureau for designing buildings on water. From 1945 to 1948, he worked in the Ministry of Engineering of Yugoslavia and State Hydrometeorology Institute. In 1948, he was elected associate professor and in 1951 regular professor of the Technical Faculty, where he worked until his retirement in 1963. He was corresponding member of SANU from 1959 and regular from 1963.

He died on June 5, 1973 in Belgrade and, according to his wish, was buried in his birth village.

***

Surname

The strange surname Pećinar originates from the nickname given to a certain Mijailo, who chose a cave (Serbian ”pećina”) in the vicinity of Ljubiš as his residence. Not for fun, but out of necessity. The Pećinar family still uses the cave, keeping cattle, agricultural equipment and memories in it.

***

Comparisons

In the work ”From Meadows to Science”, which brought Mihailo Pupin Idvorski the Pulitzer Prize in 1923, the author wrote about himself. In his book ”From Serbia to Yugoslavia”, Pećinar wrote about a period of time between the XIX and XX century, about the epopee of suffering and glory of Serbia in the Balkan and First World War, about the uniting of Yugoslavia. It is both an intimate confession and a historical document, both a chronicle of a family and an ethnological study about the archipelago of villages scattered over Zlatibor and their poor and upright people. It is also the most wonderful monument to the cruel time of growing and maturing of his generation. ”A chronicle of events as experienced and evaluated by one of their contemporaries”. This is one of the reasons the work of Miladin Pećinar should best be compared with the ”Serbian Trilogy”, written by academician Stevan Jakovljević.